In November 2022, people working in sectors ranging from tech to marketing to education were suddenly able to write any genre or length of text using only a few short prompts. The game-changing technology is, of course, ChatGPT, created by Open AI, an Artificial Intelligence and research company. Described as a “natural” language tool, ChatGPT allows people to have “human-like” conversations with chatbots, answer questions, create or summarize text and write code.

Fittingly, many people are using ChatGPT as they would a human assistant. Some use it to avoid the drudgery of email writing, maintaining databases or creating repetitive code. Some see ChatGPT as a “thinking” companion that can expertly summarize complex texts, generate ideas or create business plans. It’s true, many of ChatGPT’s “abilities” feel like magic, in particular its ability to increase the ever-monetized Productivity and Efficiency. But according to Charlie Warzel writing for The Atlantic, ChatGPT “… has upended or outright killed high-school and college essay writing and thoroughly scrambled the brains of academics… it has flooded online marketplaces with computer-generated slop… [it’s] a way for machines to leech the remaining humanity out of our jobs.” The tool does suggest a tech breakthrough, one that has (re)opened heated debates about the necessity of human-led work in the present and the future.

When Machines Rule the World

In the fall of 2023 in Berlin, I saw an exhibition titled, “NOX” by Artist Lawrence Lek hosted by the LAS Foundation. It was summarized (perhaps by ChatGPT) as “an expansive exhibition that imagines the psychological consequences of a future populated by smart systems and intelligent machines...” Being a human, I might describe the show as “tech-porn”, consisting of several budget-busting videos, and glossy luxury cars as sculptures. In Lek’s videos, passenger-less automated cars roam the empty streets of a post-human urban world. They (somehow) get into accidents with each other and speak with authoritative, mostly male, digital voices. The cars even go to therapy – when they start to perform badly, rendering their sole purpose to achieve optimal efficiency. All in all, Lek created a replica of our human world but with machines instead of people, plants, water or animals. (Did I mention there are also no females or children?) Whether Lek intended to use automated cars as symbols of our endless appetite for machine-like efficiency was unclear, but that would have been a more engaging exhibition.

Just one week later my wish was granted. I saw the film, “The Killer” (2023) directed by David Fincher. The movie follows a hired assassin (Michael Fassbinder) as he trains himself to renounce nearly every human quality or need in order to become a (killing) machine. Working in physically restrictive, high-stress and dangerous environments, Fassbinder’s character sleeps only in REM cycles, eats only the meat from McDonalds sandwiches, sits/drives/parks alone all day staring through binoculars and tries his best not to love his lover. But still, he shoots and misses. Immediately following his mistake, he enacts a series of perfected habitualized tasks designed to remove all traces of his (human) existence – a sequence that puts the most seamless of assembly lines to shame. A rented storage unit filled with containers and endless locked drawers provide him with fake passports, new clothes, license plates and hair dye. Like Lek, Fincher’s film highlights our desire to be less human — to perform (sometimes horrific) acts with immeasurable excellence, to work with ever increasing speed. In other words, to be acknowledged for our ability to deny ourselves.

Machine Power On?

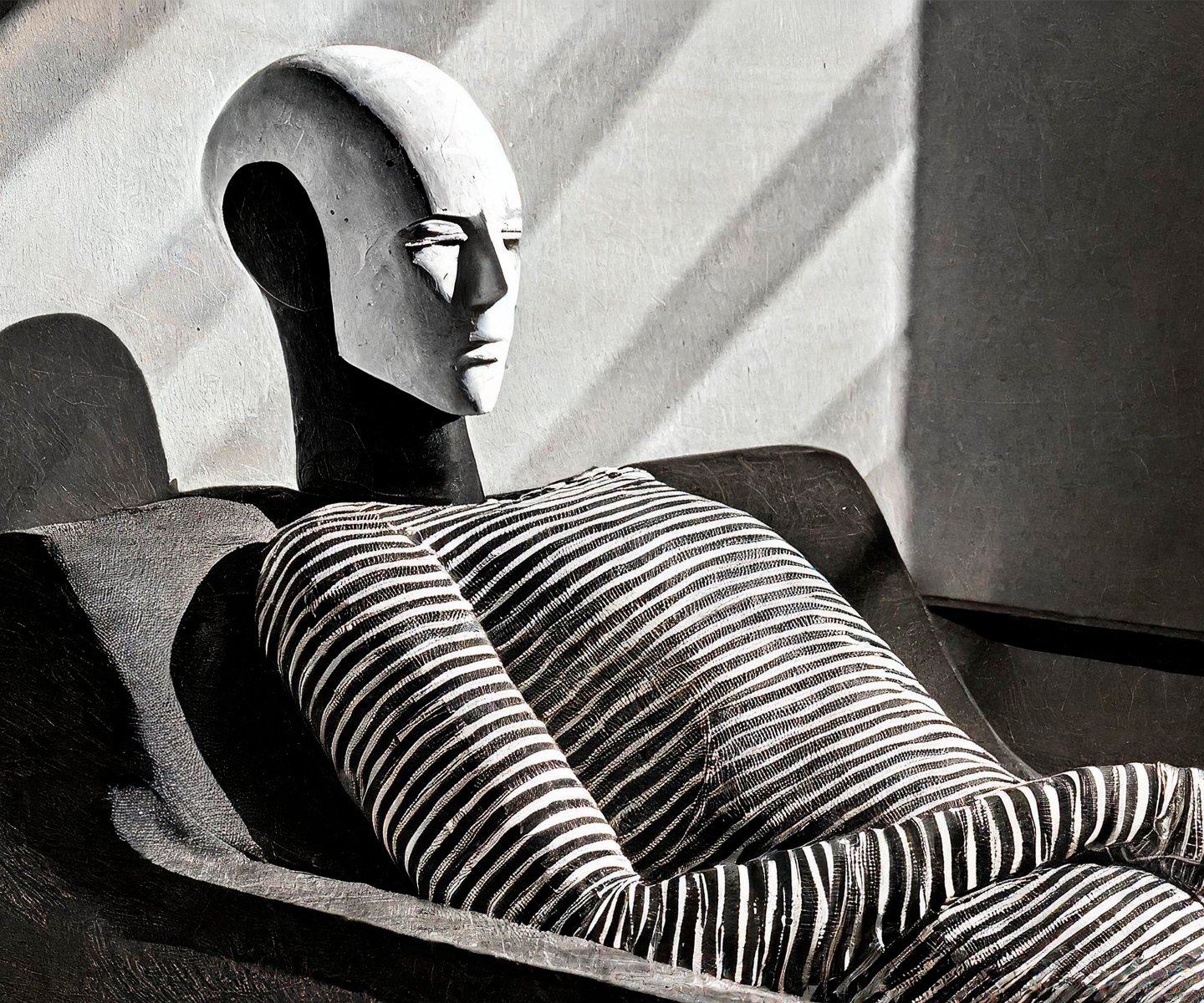

Let’s consider what might be lost when the working world becomes machine-like efficient, or even if (and when) humans aren’t working at all. Body to body relationships for one. Nuance and complexity for another. ChatGPT loves clichés and machines are made for perfection. What gets lost in-between are sensations, exceptions, feelings and spontaneity. As Warzel suggested, AI such as ChatGPT may be the beginning of an unrecognizable world to come. Considering Lek and Fincher’s creations in such close proximity to the rise in usage of ChatGPT, brings the loss of humanity, in general, and more specifically in relationship to work, into the spotlight. I wonder – in a world of increasing inhumanity (should I list the wars or injustices currently raging?) do we really need more tools to further distance us from humanness? And, will AI ever allow us something more than all-you-can-eat speed and efficiency? And will the result grant us more rest? Rest. The one thing rarely expected of machines.

– Jasmine Reimer is a Canadian writer, visual artist, and educator. Currently based in Berlin, she holds an MFA in Studio Art from The University of Guelph. Her research ranges from 18th century German and Italian grotesque to Neolithic goddess mythology to contemporary spirituality, religion, cosmology, and the occult. In general, she is interested in the construction of cultural myths, collective memory/consciousness, archetypes, and traditional and contemporary mysticism. Specifically, Jasmine focuses on the hybrid body as a powerful feminist symbol of transformation and fluidity – ecstatic, abundant, and transgressive. East Room is a shared workspace company providing design-forward office solutions, authentic programming and a diverse community to established companies and enterprising freelancers. We explore art, design, music, and entrepreneurship; visit our news & stories page to read more.